Sea Rainbow

_ Plastic-scape

2020. 3.18-3.27 Kyushu Geibunkan, Japan

by Kim Soonim

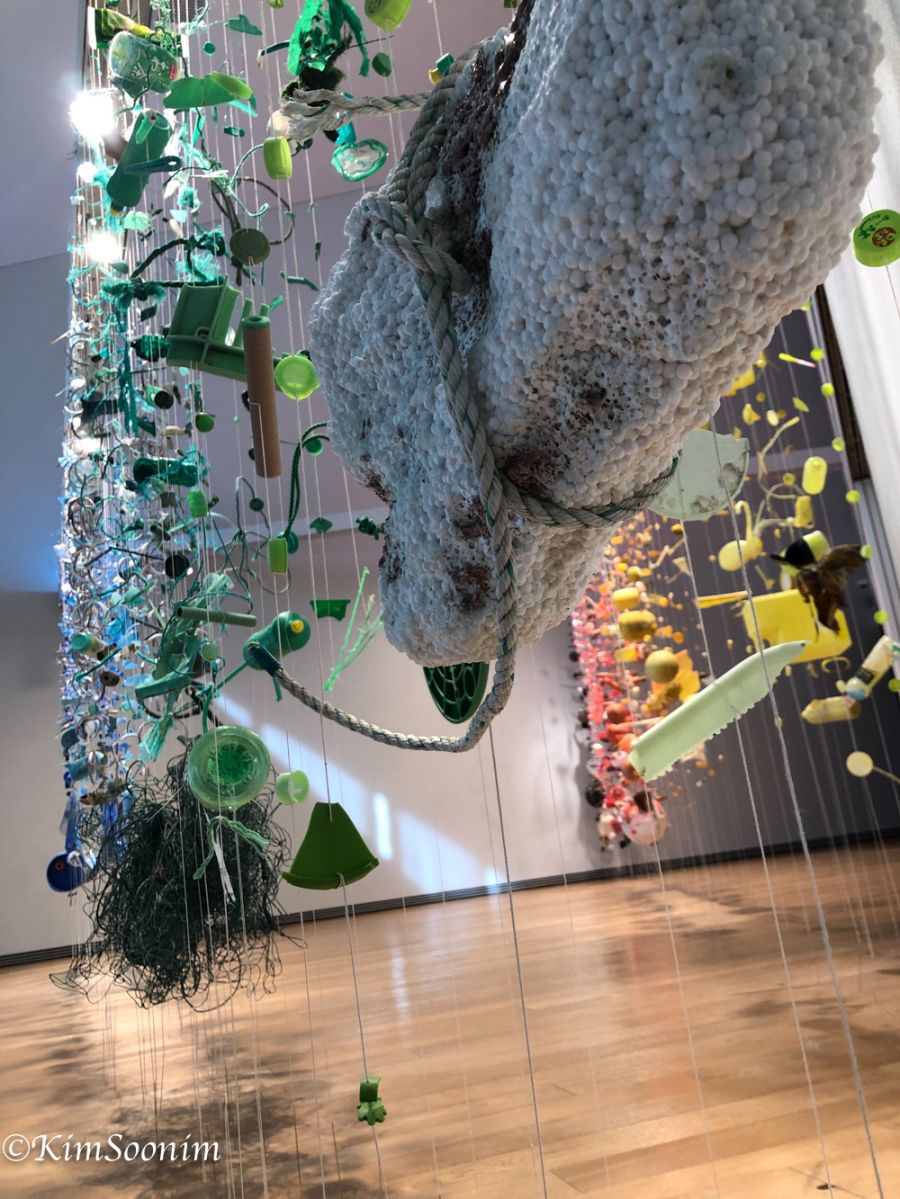

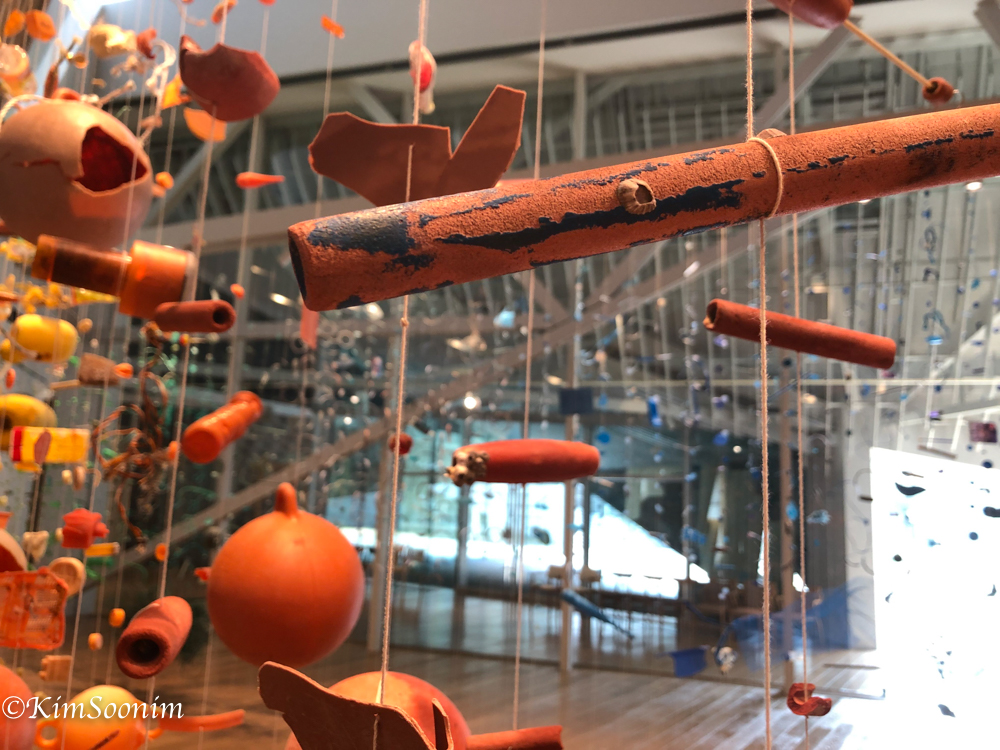

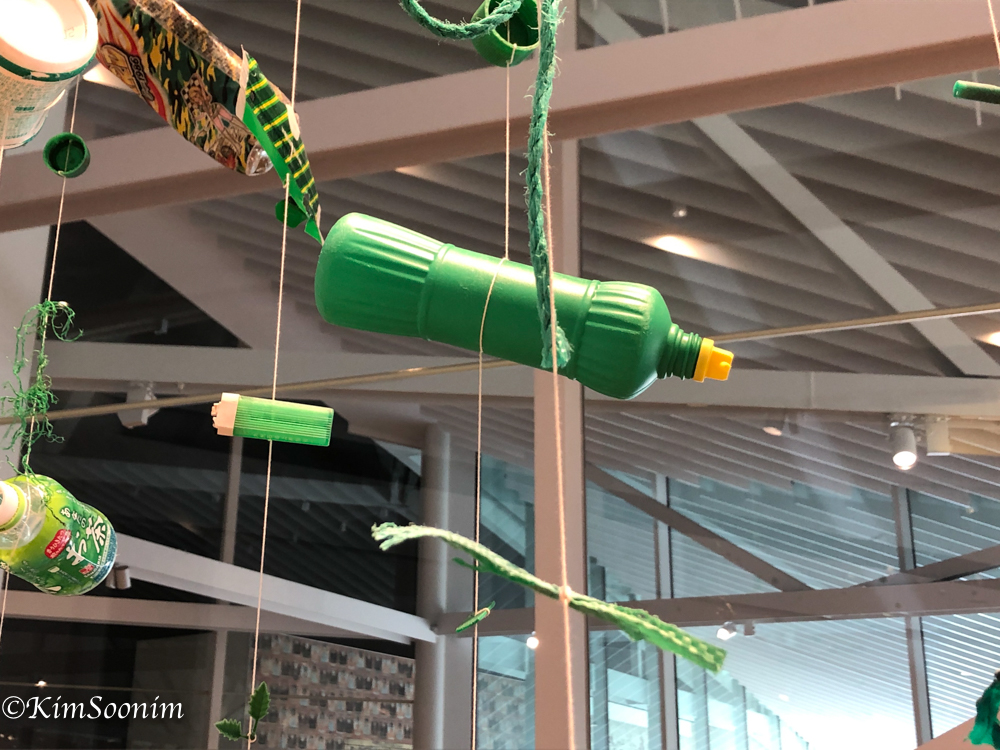

Installation work title : Sea Rainbow

Material : beach plastics on Ariake Sea and Fukuoka Beach, cotton threads, needles, motion sensor, magnetics,

Size : variable installation on Kyushu GeibunKan, Year: 2020

Video work title : The Sea of Strayer

Single Channel video

Size : 11’20’’

Year: 2020

Sea Rainbow / 바다 무지개

Rainbow of Sea plastics

Plastic-scape _ 풍경이 된 플라스틱

2019년 초부터, 아니 그 이전부터 나는 바닷가에서 보이는 색(플라스틱)들이 신경 쓰였다.(물론 이 즈음 쏟아져 나온 다큐멘터리와 여러 보고서의 영향도 있었다. 게다가 늘 디테일을 보는 습관 때문인지, 깨끗해 보이는 해변에서도 늘 플라스틱이 보였다. ) 뭔가 불편하지만 치운다고 될 것도 아니었다. 너무 많다. 그리고 너무 다양하고, 너무 작아진다. 뭔가 얘네들은 내가 매일 사용하는 것들과 모습과 색이 달라져 있고, 어쩌면 자연인 듯 위장하고 있기도 하다. 이 나(인간으)로부터 온 ‘불가촉물’, 플라스틱들을 ‘자연이 아니다’ 또는 여전히 ‘인공’이라 할 수 있을까? 대부분 플라스틱은 인공이며 자연과는 분리된 제거해야 할 독이라 생각할 것이다. 그렇다 그것은 인간으로부터 나서 인간에게 해롭다. 그런데 완벽한 분리가 가능할까? 우리의 생존은 이미 플라스틱에 너무 많이 의존한다. 우리는 매일 매순간 플라스틱을 만지고, 입고, 먹고, 마시고, 숨쉰다. 지구 어디에나 있고, 우주에도 있으며, 내 피, 세포 속에도 있다. 이미 자연화 된 이들을 우리는 어떻게 받아 들어야 할까? 나에게 답이 있는 건 아니다. 나도 잘 모른다. 다만 작가로서 내가 관찰하고 마음 가는 이것을 발견한 모습으로 전시장에서 제시해본다.

우리는 매일 반짝이는 새 플라스틱들을 사용하고 버린다. 일단 한번 쓰레기통에 들어가면 이 아이들을 보는 일에 마음이 불편해지기 시작한다. 깨끗하게 눈앞에서 치우면 없었던 것처럼 새로워진다. 하지만 이 아이들은 사라지는 것이 아니다. 버려진 아이들은 여행을 한다. 바람을 타고 날아 하늘을 오르기도 하고, 물위를 이리저리 흐르기도 하고, 작은 생물들의 집이 되어주기도 하고, 먹이가 되기도 하며, 풍경을 이루기도하고, 어딘가에 깊이 쌓이기도 한다. 긴 여행을 하는 이들은 사라지는 것이 아니다. 여행을 하며 여러 곳을 가고, 많은 이를 만나며, 구르고 구르다 다시 돌아온다. 나(사람으)로 인해 한번 태어나고, 삶을 함께한 이상 다시 돌아온다.

나는 플라스틱을 없애야 한다거나 적대시 하는 일에 비관적이다. 환경교육으로 해결할 수 있다는 로멘틱한 꿈은 애초에 꾸지 않는다. 너무 적대시해서 플라스틱을 쓸 수 밖에 없는 사람들을 죄책감에 들게 하는 것도 방법이 아니다. 죄책감은 이 문제를 더욱 사람들로부터 멀어지게 한다. 다만 나는 이 아이들이 너무 많이 생산되고, 쉽게 쓰여지고, 귀하게 대접받지 못하는 것이 불편하다. 적어도 나에게 이 플라스틱도 존재하는 ‘물(物)’이다. 인정할 건 인정하자. 이들은 이미 우리의 풍경이 되었다.

설치 방식은 어디에서 왔나.

후쿠오카의 큐슈예문관에 지원한 것도 한국의 남해안과 중국의 동쪽 해안이 만나는, 같은 바다를 가진, 다른 문화의 사람들을 만나고, 내가 본 해안과 그들의 해안을 경험하며, 나름의 시각적 표현방법을 찾기 위해서였다. 어디를 가고 싶냐는 말에, 막연하게 ‘해변’이라고 했고, Tsuru상과 Sakai상이 데리고 간 아리아케 바다의 해변에서 바다와 그 바다에 기대어 사는 사람들이 만들어놓은 풍경들을 보았다. 돌아오는 길에 검은 고양이 한 마리가 차도를 가로질렀는데, 불길한 상징이라며 차안이 떠들썩했다. 너무 예쁜 고양이에게 억울한 이미지 같다. 차가 돌면서 잠깐 하늘에 무지개 조각이 비친다. 내가 흥분해 말하자 길조(good luck)라 한다. 좋은 일이 있을 거라며…

하늘높이 떠서 빛에 의해 생겨나는 무지개는 왜 사람들이 이렇게들 좋아할까? 그러고 보면 물 위에 기름이 뜰 때도 무지개가 생긴다. 좋은 일이 아니어도 보기에 예쁘긴 하다.

3월 규슈는 봄은 맞이하며 집마다 사게몬(사게몬은 일본 후쿠오카현 야나가와시에서 전해지는 풍습이다. 매는 장식품으로 소녀가 태어난 집에서 행복을 기 원하기 위해 매단다_위키백과)이 있다. 아이들의 꿈을 위해 어른들이 만들어 장식하는 아름다운 전통이다. 보기에도 아름답고 즐겁다. 매달려 흔들리는 조각들은 섬세하고 아름다우며 그 아래 하늘을 나는 아이들의 형상이 흔들린다.

이번 나의 설치작업은 도착한 첫 주 이곳에서 만난 여러 문화와 나의 작업 언어가 만나, 실험하게 되었다. 아이들의 꿈을 위한 어른들의 장식품 형태에서 가지고 온 플라스틱 설치 방식, 전체를 무지개 색으로 분류하고 배치하여 멀리서 보면 아름다운 형상의 설치이지만, 가까이서 보면 시간과 환경을 그대로 감당해낸 바다로부터 온 플라스틱들을 만나게 된다. 하나하나 해변에서 만나고, 미술관으로 가지고 와서 만지고, 씻고, 닦아, 귀하게 조명까지 주면서 사람들을 만나도록 한다. 고생 많았던 플라스틱 조각들, 하나하나 이야기가 있을법한 조각들, 하나하나 내 집에, 내 주변에 있을 또는 있었을 조각들을 만나게 된다.

영상 작업은 이 플라스틱을 만난 바닷가를 보여주는데, 처음 도착했을 때 이 바다들은 무척 깨끗해 보였다.. 플라스틱을 충분히 구할 수 없을 것이라 걱정했는데, 자세히 보니 곳곳에 숨어 있다. 수집과정에서 숨은 바다플라스틱들을 전시장에서 영상으로 설치하였다.

플라스틱들은 바다를 여행하면서, 자연을 흉내내고, 닮아가고, 자연이 되어간다. 그들은 이미 우리의 풍경이 되었다.

이번 설치작업에서는 해변에서 만난, 다양한 종류와 색을 가진, 플라스틱을 가져와 깨끗하게 물로 씻고, 손질하였다. 그리고, 규슈예문관 공간의 구조와 질감, 빛의 방향 시간에 따른 공간변화 등을 고려하여 플라스틱을 설치 했는데, 입구부터 동선을 만들고, 입구에는 센서에 의해 관람객이 진입하면 파도소리가 일정시간 들리도록 설계였다. 입구부터 짙푸른 빛으로 시작해서 뽀족한 벽으로 초록으로 이어지고 다시 노란색으로 돌아 주황과 붉음 그리고 검정까지 색을 분류한 플라스틱을 서로 꿰어서 설치하였다.

2020. 3. 18. By Kim Soonim

이 작업은 자연재료로 자연현장에서 작업하던 작가에게 늘 신경쓰이던 플라스틱이 인간이 만든 재앙이긴 하나, 이미 사람에 의해 자연화 된 풍경이라는 것을 보여주고자 한 작가의 <바다 그림자>프로젝트의 첫 번째 설치이다.

우리 삶은 플라스틱에 너무나 의존하고 있고, 그 의존을 대체할 기술이 부족하다면, 적어도 인식해야한다. 인식은 불편함의 시작이며 불편함은 변화의 시작이다. 20200513 by Kim Soonim

Rainbow of Sea Plastics

Ever since early 2019, or perhaps even earlier, I have been paying attention to colors (plastics) that I see in the sea. I’m sure that I was influenced by various documentaries and reports that came out around this time. However, I was always able to see plastics in the sea, even when the water appeared clean, thanks to my habit of constantly observing details. In terms of trying to solve the problem, these plastics cannot be simply filtered out, since there are too many and it would be far too inconvenient. Moreover, they vary widely in size and shape, with most of them actually being too tiny. Somehow, they seem different from the plastics that I use daily, both in color and shape, thus disguising themselves in nature. Although these ‘untouchable’ plastics are ‘not natural,’ can they still be considered ‘artificial?’ Most plastics are inherently artificial and regarded as materials to separate and disposed of. They both originate from and are detrimental to humans. However, is it even possible to separate them perfectly? Our lives already heavily depend on plastics. Every moment of every day, we touch, use, eat, drink, and breathe plastics. They exist everywhere on Earth and even infiltrate our blood at the cellular level. How can we accept naturalized plastics? I do not have a definite answer, but I present my ideas within the exhibition space according to what I have observed and following my heart as an artist.

We use and throw away shiny new plastics every day. After they are relegated to the trash bin, we find it inconvenient to look at them. Once we abandon them, the begin to travel. Some fly up in the sky, lifted by the wind, while some float on the water’s surface. They may serve as houses for small creatures, become eaten as food, blend into the landscape, or accumulate somewhere en masse. Despite the long journeys they endure, this does not necessarily mean that they disappear. They visit many places and meet other plastics during their travels, only to return after continuously moving around. As long as they are born because of humans and live together, they return.

I am pessimistic about getting rid of plastics as well as harboring hostility toward them. I never had any idealistic notions of resolving the issue through environmental education. Making people feel guilty, even though they have no choice but to use plastic, and antagonizing them is not a reasonable way to deal with the problem. Feeling guilty only leads to people avoiding the issue entirely. However, I feel uncomfortable with the fact that plastics continue to be excessively produced, easily purchased, and poorly managed. To me at least, plastics exist as ‘objects.’ Thus, we ought to acknowledge that they are part of our environment.

The primary motivation for my application to Kyushu Geibun-kan in Fukuoka was to meet people of different cultures who all share the same sea, and to convey my own experiences acquired on the coast by visually expressing myself in the place where Korea’s southern coast and China’s eastern coast converge. When asked where I wanted to go, I responded with a vague answer, “the coast,” and Mr. Tsuru and Mr. Sakai guided me to the Ariake Sea, where I observed the coastline and surrounding landscapes created by people who live within symbiosis with the coast. On the way back from the sea, a black cat crossed the road and everyone in the car declared that it was a bad omen, which caused quite a stir among the other passengers. I thought it was an unfair judgment of such a cute cat. Once the car turned the corner, however, a rainbow appeared in the sky. When I excitedly pointed it out to the others, they said it was good luck and a sign of good things to come. Why is a rainbow high in the sky, which is a phenomenon created by light, so incredibly loved by people? Come to think of it, a rainbow is also created when oil floats on water. Although this is not necessarily a good thing, it still can be considered beautiful.

In March, every house in Kyushu participates in the sagemon festival in which people wish for happiness by hanging ornaments on houses where girls are born. (This custom has been passed down for generations in Yanagawa City, Fukuoka Prefecture, according to Wikipedia). It is a beautiful and pleasing tradition for grown-ups to make ornaments for children’s dreams. The hanging and swinging sculptures are elaborate and lovely, and figures of children flying in the sky stay underneath.

On this occasion, my installation pertains to an experiment I conducted in which various cultures intersected with language during the first week of my arrival. It is an installation of plastics as ornaments made by grown-ups for children’s dreams. By dividing and situating entire objects within the colors of the rainbow, the installation appears to be a beautiful instrument from a distance, while up close viewers can encounter plastics from the sea that have weathered the ravages of time and mother nature. All of the plastics were gathered from the coast, brought to the art museum, touched and washed, and instilled with value by illuminating them. In this way, audiences can encounter pieces of plastic that may have withstood countless hardships, each with its own story, ultimately arriving here.

Video link: https://youtu.be/voBAR27oqis

Video title: The Sea of Strayer

Single-channel video, 11′20″, 2020

This video shows the sea where these plastics come from. When I first came to the sea, it looked very clean. I was actually worried that I might not find much plastic there, but on closer inspection, I found that plastics were hiding everywhere. In the exhibition space, I installed a video of these hidden plastics that I found while collecting.

As they travel across the sea, they begin to imitate and resemble nature, before finally becoming a part of it as they transform into fragments of our surroundings.

For this installation work, I brought plastics of various shapes and colors that I encountered on the beach, rinsed them with water, and thoroughly cleaned them. I then installed those plastics by considering the structures and textures of the spaces at Kyushu Geibun-kan as well as subtle spatial changes that depend on the direction of light and passage of time, creating a design in which moving lines are considered from the entrance and viewers can hear the sound of waves. The entrance is enveloped in deep blue, which leads to a pointed wall in green, and the remaining plastics are divided into bands of color such as yellow, orange, red, and black, all of which are woven together for this installation.

2020.3.18 by Kim Soonim